Model#

Definitions#

The sets and their associated parameters are shown in Table 1. We elaborate on a few aspects of this model. If the working capacity at an airport is reached, then a plane will wait for an open slot. Once the airplane starts processing, it will need a fixed amount of processing time \(\processtime{p}\), regardless of whether cargo is being loaded or unloaded. As in [2], we impose two deadlines: one is a soft deadline \(\softdeadline{c}\) by which the cargo is expected to be delivered, and one is a hard deadline \(\harddeadline{c}\) after which the delivery is considered missed and no longer useful.

One of the parameters we introduce in our ICAPS 2024 iteration of the Airlift Challenge is being able to assign priorities to agents. The priority of an agent is assigned when giving it an action. Priority replaces process, and agents are automatically processed for loading/unload when it is their turn in the queue. Priority dictate in what order airplanes will be processed when they land at an airport. The priority cannot be updated when an agent has been placed in the queue, and the lowest valued entry is retrieved first. The number of priorities allowed within the action space is set to the number of agents in a scenario. The implementation of the queue uses the PriortyQueue class and more information on it can be found at https://docs.python.org/3/library/queue.html.

Set |

Description |

Associated Parameters |

|---|---|---|

\(\Airports\) |

Airports |

For airport \(a \in Airports\):

|

\(\Routes\) |

Routes between airports |

For route \(r \in \Routes \subseteq \Airports \times \Airports\):

|

\(\Airplanes\) |

Airplane |

For airplane \(p \in \Airplanes\):

|

\(\Cargos\) |

Cargo items |

For cargo item \(c \in \Cargos\):

|

Dynamic Features#

We start by providing a list of variables. For brevity, we only identify key variables rather than provide an exhaustive list. Given airplane \(p \in \Airplanes\) and airport \(a \in \Airports\), Table 2 defines variables and sets that reflect the environment state at time \(t\).

Variable / Set |

Description |

|---|---|

\(\currentairport{p}{t} \in \Airports\) |

The current location of airplane \(p\). |

\(\AvailableRoutes{t} \subseteq \Routes\) |

Set of available routes. |

\(\CargoOnPlane{p}{t} \subseteq \Cargos\) |

The set of cargo loaded on airplane \(p\) |

\(\CargoAtAirport{a}{t} \subseteq \Cargos\) |

The set of cargo stored at airport \(a\) |

\(\AirplanesAtAirport{a}{t} \subseteq \Airplanes\) |

The set of planes processing at airport \(a\) |

The following dynamic events may occur:

A new cargo order is added to set \(C\).

Route \(r \in R\) becomes temporarily unavailable for landing or takeoff (e.g., due to weather). Flights already en-route will still complete the flight to the destination.

The available actions for each agent are shown Table 3. Note that actions may become invalid as the state of the model evolves (for example an airplane’s destination may become unreachable).

Action |

Description |

|---|---|

\(\priority{p}\) |

Integer indicating the priority of the airplane. This effects the queue order when processing at airports. Lowest value is retrieved first. |

\(\cargotoload{p} \subseteq \CargoAtAirport{\currentairport{p}{t}}{t}\) |

Boolean indicating whether or not route \(r\) is available. |

\(\cargotounload{p} \subseteq \CargoOnPlane{p}{t}\) |

The set of cargo unload from the airplane. |

\(destination\) \(\in \{ a_2 \in \Airports | (\currentairport{p}{t}, a_2) \in \AvailableRoutes{t} \}\) |

The next destination of the airplane. |

Airplane State Machine#

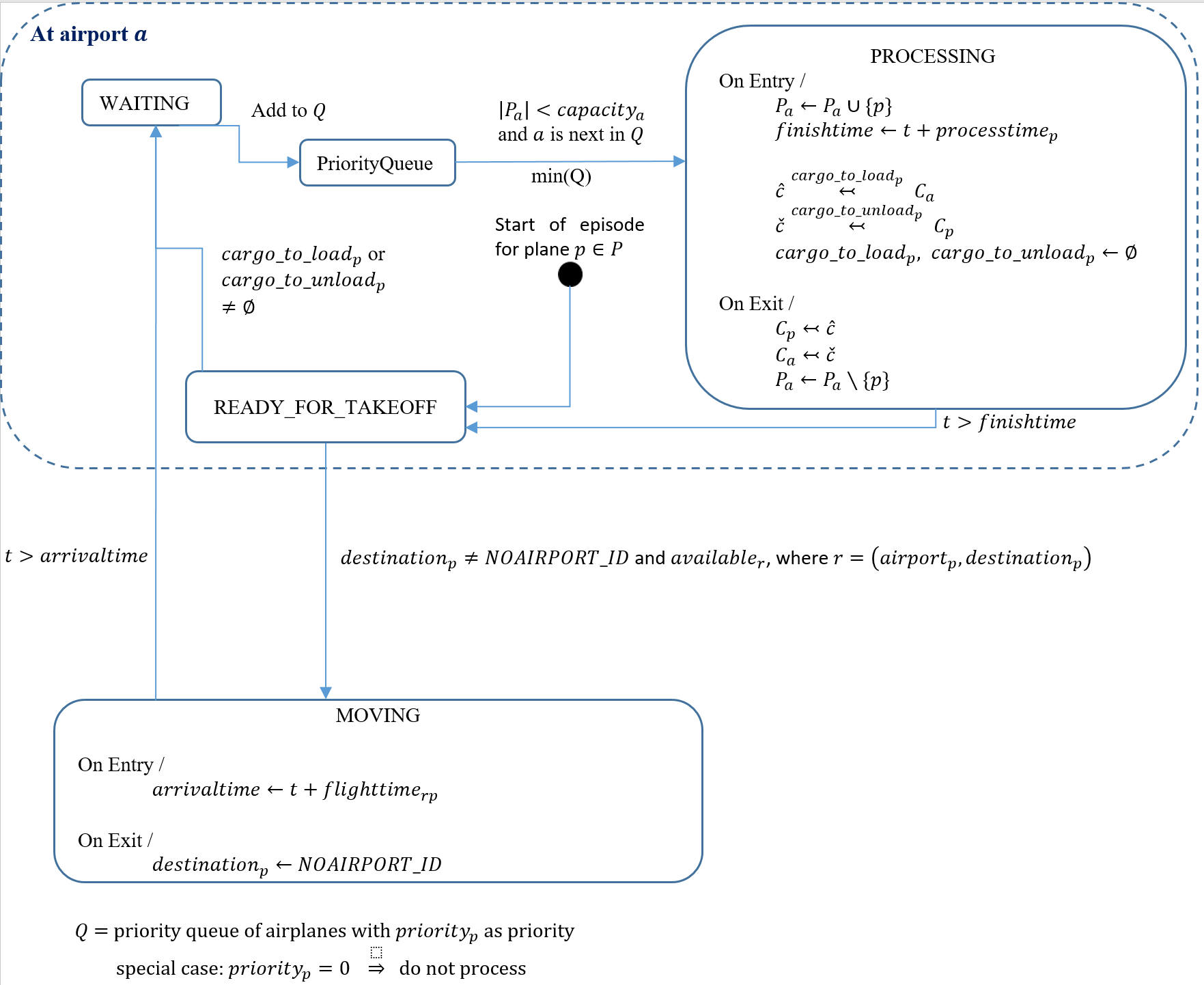

A state machine for the airplane is shown in Fig. 1 (see a list of airplane states with descriptions). Airplanes will process before they can before they are fully fueled and ready to take off. Although we do not explicitly model fuel usage, the processing state introduces a wait typically needed for refueling and other maintenance. If airport capacity is reached, the airplanes will process according to their priority and in the order in which they arrived. The agent may choose to load/unload cargo during processing, or may let the airplane process without moving cargo. While the cargo is being loaded, it will be removed from the airport cargo set during processing, and then added to the airplane cargo set when finished. A similar process is followed for unloading cargo. Once ready for takeoff, the airplane will take off for the specified destination. The agent may specify additional cargo to load/unload and the airplane will re-process. The airplane will only take off if the route is available, i.e., if a random event has not taken the route offline. While in-flight, the airplane moves at a uniform rate along the route, set according to the flight time for that plane on the given route. The agent cannot issue any actions during the flight. Once it reaches an airport, the airplane will land and return to a waiting state pending further action by the agent.

Fig. 1 Airplane state machine. Time parameters are omitted from events for clarity. The transition labels indicate the condition required for the transition to occur. State transitions are evaluated at each time step. The notation \(\mathbf{A} \stackrel{\mathbf{B}}{\leftarrowtail} \mathbf{C}\) indicates that the elements in set \(\mathbf{B}\) are removed from set \(\mathbf{C}\) and added to set \(\mathbf{A}\) (if \(\mathbf{B}\) is omitted, all elements are moved from set \(\mathbf{C}\) to \(\mathbf{A}\)).#

Metrics#

We base the score and reward on three raw metrics:

where \(\Indicator{\cdot}\) is the indicator function, \(\actualdelivery{c}\) is the actual time when the cargo is delivered (or \(\infty\) if the delivery never occured), and \(\numflights{r}{p}\) is the number of flights by plane \(p\) over route \(r\). The number of missed deliveries is captured by (1). For deliveries that are not missed, (2) indicates the amount of time by which these deliveries miss the delivery deadline. The cost incurred by airplane \(p\) flying routes during the course of the episode is identified by (3). We note that although the cost may be primarily driven by fuel usage, it can also quantify other costs.

In order to encourage more uniformity across scenarios, we derive two scaled metrics. First, we scale the lateness so that it’s value will range between 0 and 1:

Second, we scale the flight costs of each airplane against the diameter of the route map graph, the number of cargo generated \(\totalcargo\), and the capacity of the airplane. Specifically, the total scaled flight cost over all planes is defined as

where \(\routemapdiameter{p}\) is the diameter of the largest connected component of airplane \(p\)’s route map.